Blog | 25 Mar 2021

China’s opportunity to show climate leadership in 2021

Tom Rogers

Associate Director, Capital Projects and Assets Consulting

Few policy issues are attracting more attention than how to leverage the post-COVID recovery to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy. Europe’s Green Deal aims to mobilise €1trn in sustainable investment over the coming decade, President Biden campaigned on a promise to unleash $2trn in clean investment in the US over his first term, and Japan’s ruling party has urged its leadership to follow suit with a fund “comparable to global standards” to help finance Japan’s low-carbon transition.

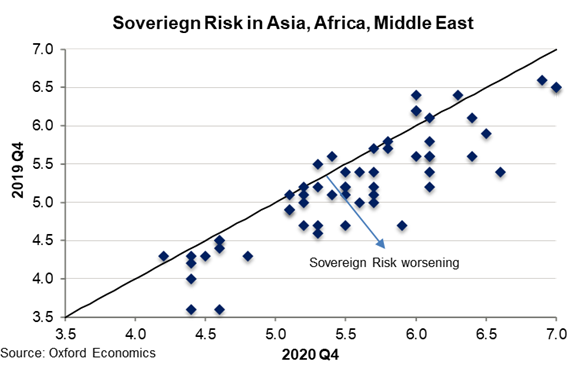

These major investment programmes are a key step to a low-carbon future. But financing the transition might be less daunting in advanced economies—where the burden of servicing government debt has consistently eased through the past couple of decades—than in emerging economies, where sovereign risk has risen over the last year. Even though financial conditions for emerging markets remain relatively favourable for now, governments in emerging economies will be conscious of the need to narrow fiscal deficits, reduce debt burdens, and steer key sovereign risk metrics back in a favourable direction. So financing the transition may take a back seat to balancing the books, at least in the short term.

The current economic landscape also provides China with an important opportunity—to deliver on President Xi’s 2019 pledge to build “high-quality, sustainable, risk-resistant, reasonably priced, and inclusive infrastructure” across the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Our 2019 report, Belt and Road Green Finance Index, highlighted the financial constraints many countries in the Belt and Road will face in shifting to low carbon—challenges that have only intensified by the events of the past year. But our report also looked at the potential role for China and other BRI members to support this transition via financial support and technological diffusion.

The current economic landscape also provides China with an important opportunity—to deliver on President Xi’s 2019 pledge to build “high-quality, sustainable, risk-resistant, reasonably priced, and inclusive infrastructure” across the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Our 2019 report, Belt and Road Green Finance Index, highlighted the financial constraints many countries in the Belt and Road will face in shifting to low carbon—challenges that have only intensified by the events of the past year. But our report also looked at the potential role for China and other BRI members to support this transition via financial support and technological diffusion.

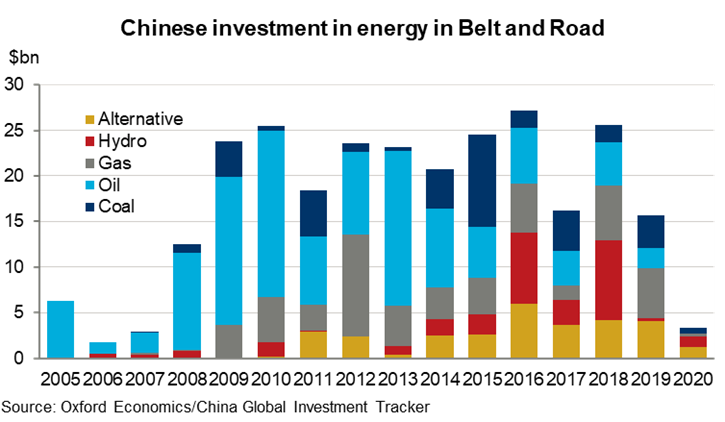

What specifically could China do? One option would be to accelerate investment in clean energy along the Belt and Road, which understandably stalled in 2020. But even before the pandemic, alternatives only formed a small part of China’s outbound energy investment. This contrasts with its domestic achievements—China has gone from almost a standing start in 2015 to having as much installed solar capacity as the US and Europe put together, and in 2019 added more than Japan, India, South Korea, Australia and Vietnam combined. By providing the financial inputs and know-how, and working with local labour, China could support a powerful short-term driver of recovery. For example, an analysis of Cyprus by the World Bank found that incentivising solar capacity installation had the greatest short-term employment impact among a range of “Green Recovery” measures, and by far the greatest long-term carbon savings.

Supporting short-term demand at the same time as accelerating the transition to clean energy would clearly be a win-win for China’s Belt and Road partners, as well as the global recovery and transition to low carbon. China could prioritise this in its outbound investment though 2021, and arrive at November’s COP 26 having demonstrated a leadership role in supporting the transition in emerging economies. Will China take up the challenge?

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

The Green Leap – Project bankability takes centre stage

The report argues that enhancing project bankability should become a main policy priority as part of climate investment endeavors.

Find Out More

Post

What does the critical minerals boom mean for Africa? | Greenomics podcast

As demand grows for critical minerals like cobalt, copper, and lithium, African nations are navigating opportunities and risks—from boosting local employment to managing geopolitical tensions and environmental concerns.

Find Out More

Post

Toward a global carbon pricing system

Fragmented carbon markets and the risk of carbon leakage are jeopardizing progress toward global net-zero targets. A major challenge lies in the lack of coordinated policies to align around a unified carbon price. Oxford Economics, in a study for the Hinrich Foundation, highlights how regional carbon markets could offer a practical path toward more effective global pricing.

Find Out More