Legacy cities: historic centres that must relearn lessons in growth

The 1,000 cities in Oxford Economics’ Global Cities Index are locked in a state of continuous transformation, driven by evolving economic forces, shifts in demographics, climate change, technological innovation, and growing urban diversity. But as the balance between manufacturing, services, and knowledge-based industries has altered, resources, companies, and people have become concentrated in select metropolitan areas—leaving others behind.

Cities that have successfully adapted to these changes are enjoying significant growth, while others—which we have called Legacy Cities—face challenges to develop new economic foundations, attract residents, and reposition themselves for contemporary success.

What makes a legacy city?

There is no single accepted definition for the term Legacy City, but it is often used to describe former industrial powerhouses and hubs of business, retail, and services that have seen endemic loss of jobs and population. We have used a more complex set of criteria that aim to capture the interaction between demographic changes, migration, and economic growth. We have defined a Legacy City as having:

- a shrinking population;

- an old-age dependency ratio of at least 30 elderly per 100 working-age individuals;

- a foreign-born population of less than 15% of the total; and

- annual economic growth of less than 1.5%.

What unites these cities, therefore, is a demographic challenge from ageing and falling populations, which has resulted in a slowdown or even stagnation in economic growth. This is aggravated by a low share of foreign-born residents, which means they cannot attract enough new migrant workers to offset the population losses from low fertility rates.

The challenge: falling populations and slower growth

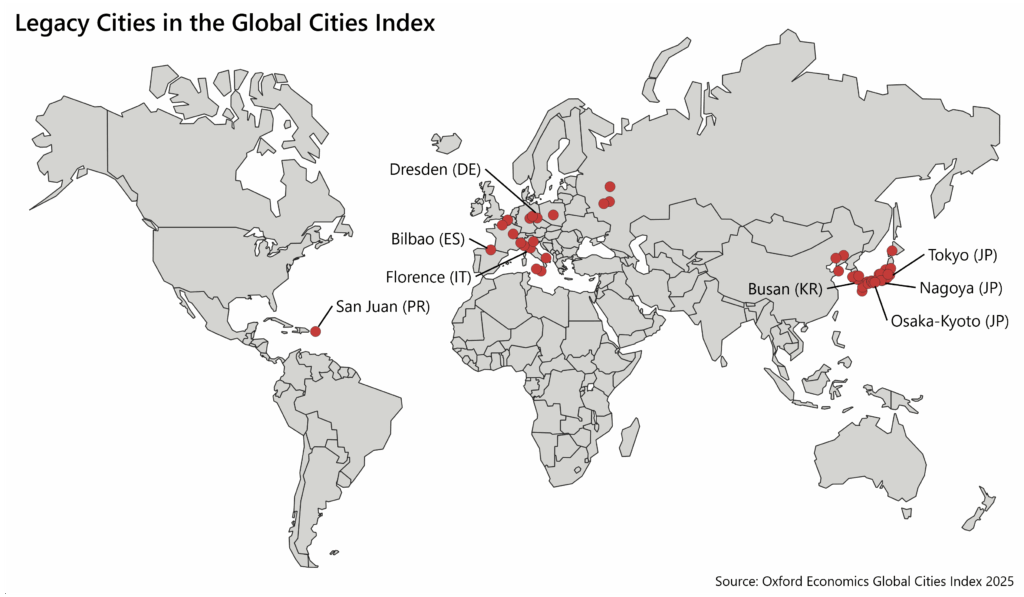

We have identified 50 Legacy Cities stretching across the globe with the majority located in western Europe and east Asia.

As the country with largest number of Legacy Cities, Japan’s experience sheds a light on these factors. It has historically had among the lowest migration flows relative to its population, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. And OECD data show that Japan has one of the lowest shares of foreign-born population among its member countries—2.2% in 2021 compared with an OECD average of 10.4%.

Osaka-Kyoto, the second-largest metropolitan area in Japan, is a case in point. Continuing economic slowdown and maturing populations have left Legacy Cities underperforming their other developed city peers in terms of Economics and Human Capital. While it ranks at 100th in the index, it ranks just 131st on Human Capital and 238th for Economics.

According to a detailed independent academic analysis, the city is an advanced example of a population starting to decline at the metropolitan scale: the authors use figures from the OECD showing that the working-age population declined from 12.2 million in 2001 to 10.4 million by 2018. Oxford Economics’ data show an a further 2.3% decline since that year, with a forecast for a decline of almost 15% over the 25 years to 2050. Looking in particular at new towns within the metropolitan area, the study found that population decline was associated with an urban transformation from houses to healthcare facilities to cater for an ageing population. This was echoed by another study that found the decline in the Osaka Metropolitan Area had hit its outlying suburban areas especially hard. These distant suburbs face population loss and weakening activity due to a combination of their remaining residents ageing quickly and the region’s manufacturing sector shrinking.

Moving to northern Italy, the picture is starker still in the Italian city of Turin, which ranks 292nd in the index, but whose headline position is undermined by its ranking at 448 for Human Capital and 447 for Economics. The host of the motorcar giant FIAT, the decline of manufacturing during the 1980s and 1990s resulted in significant employment cuts, especially in car manufacturing, and the city has struggled with elevated joblessness, particularly affecting younger residents. The city’s population has suffered a reduction of 2.5% between 2010 and 2024, falling from around 1.74 million to below 1.70 million over those 14 years, according to Oxford Economics data. The city has become older with an old-age dependency ratio—the population aged 65+ divided by the working-age population (15-64)—in 2010 of 34.8 rising to 42.3 by 2024 and forecast to accelerate to 64.0 by 2050.

Opportunity: building on the cultural and historical legacy

As the name implies, Legacy Cities have powerful backstories that imbue them with historical and cultural significance, giving them strengths that can drive renewal and revitalisation. These regeneration efforts often include repurposing former industrial spaces and vacant downtown areas into new cultural districts, parks, and other mixed-use spaces to attract new residents and improve quality of life.

This applies to the two cities highlighted in this blog. As the imperial capital of Japan until the middle of the 19th century, Osaka-Kyoto was also the country’s centre for industry until the process of deindustrialisation took hold. More recently, it has flourished as a tourist destination, attracting praise from the World Bank for embracing emerging businesses and fostering creative sector growth. This distinctive strategy for city development—stimulating economic expansion while successfully maintaining cultural heritage—has drawn global interest: its tourism model was hailed at UNWTO/UNESCO World Conference on Tourism and Culture in 2019.

Turin is a city with a rich history, evident in its architecture, urban planning, and cultural offerings, including its iconic Baroque architecture and the legacy of its automotive industry, according to the Academy of Urbanism. The city authorities used the 2006 Olympic Winter Games as an impetus for urban transformation, attracting national and transnational resources, both public and private. In the 2010s, the city initiated urban renewal initiatives aimed at converting derelict former industrial areas into innovative spaces for creative urban experimentation and community development. Professor Anne Power of the London School of Economics has said that, despite its challenges, Turin has become “one of the most often used examples of a city turn-around”.

Conclusion: a route to recovery

While the traditional industries that originally shaped these cities may no longer exist, Legacy Cities continue to play a vital role in their host countries’ economic vitality. Their enduring significance demonstrates that they still matter greatly for national economic health. For successful urban renewal, these cities need to leverage their existing strengths to enhance their market position and develop fresh sources of economic growth.

Although each legacy city confronts distinct obstacles, they also possess distinctive strengths that can be harnessed for success in today’s world. The Global Cities Index reveals that these cities can study successful examples and apply those insights to develop effective approaches for thriving in our fast-evolving global landscape.

In this webinar, our panel of experts will outline the key results from this year’s update and will discuss major trends impacting cities around the world—from AI to trade wars to climate change.

The Oxford Economics Global Cities Index ranks the largest 1,000 cities in the world based on five categories: Economics, Human Capital, Quality of Life, Environment and Governance. Underpinned by Oxford Economics’ Global Cities Service, the index provides a consistent framework for assessing the strengths and weaknesses of urban economies across a total of 27 indicators. To our knowledge, this is the largest and most detailed cities index in the industry. To download the full report, please fill out the form below.

Tags:

Related Reports

A region of expansion and inequality: The highs and lows of Southern Asian cities

Our Global Cities Index shows that whilst Southern Asian cities do not top the overall rankings, they are important global players, with particularly strong economic performance.

Find Out More

Industrial Hubs: Finding opportunity amid the challenges

Although each legacy city confronts distinct obstacles, they also possess distinctive strengths that can be harnessed for success in today's world. The Global Cities Index reveals that these cities can study successful examples and apply those insights to develop effective approaches for thriving in our fast-evolving global landscape.

Find Out More

Tariffs and tensions are reshaping city economies

Tariff policies, rising geopolitical tensions and unprecedented uncertainty are putting pressure on cities and regions across the world.

Find Out More

The virtuous cycle of culture and prosperity in the world’s cities

Despite its breadth and intangibility, the impact of culture is revealed through our in-depth analysis of global city economies, and the fact that almost half of the world’s top 50 cities in this year’s Global Cities Index are in fact, Cultural Capitals.

Find Out More